[ad_1]

For years, some cybersecurity defenders and advocates have called for a kind of Geneva Convention for cyberwar, new international laws that would create clear consequences for anyone hacking civilian critical infrastructure, like power grids, banks, and hospitals. Now the lead prosecutor of the International Criminal Court at the Hague has made it clear that he intends to enforce those consequences—no new Geneva Convention required. Instead, he has explicitly stated for the first time that the Hague will investigate and prosecute any hacking crimes that violate existing international law, just as it does for war crimes committed in the physical world.

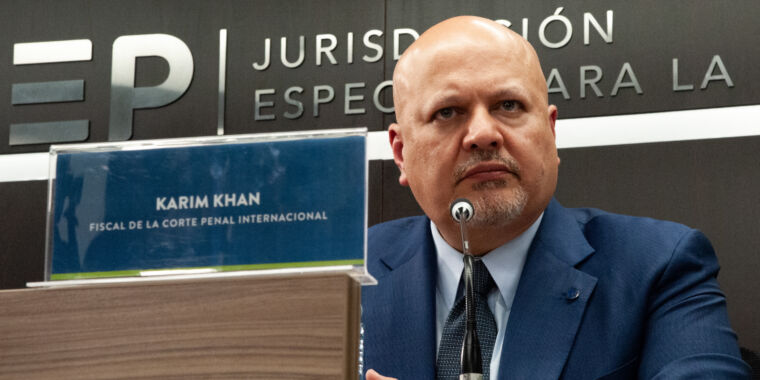

In a little-noticed article released last month in the quarterly publication Foreign Policy Analytics, the International Criminal Court’s lead prosecutor, Karim Khan, spelled out that new commitment: His office will investigate cybercrimes that potentially violate the Rome Statute, the treaty that defines the court’s authority to prosecute illegal acts, including war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide.

“Cyberwarfare does not play out in the abstract. Rather, it can have a profound impact on people’s lives,” Khan writes. “Attempts to impact critical infrastructure such as medical facilities or control systems for power generation may result in immediate consequences for many, particularly the most vulnerable. Consequently, as part of its investigations, my Office will collect and review evidence of such conduct.”

When WIRED reached out to the International Criminal Court, a spokesperson for the office of the prosecutor confirmed that this is now the office’s official stance. “The Office considers that, in appropriate circumstances, conduct in cyberspace may potentially amount to war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and/or the crime of aggression,” the spokesperson writes, “and that such conduct may potentially be prosecuted before the Court where the case is sufficiently grave.”

Neither Khan’s article nor his office’s statement to WIRED mention Russia or Ukraine. But the new statement of the ICC prosecutor’s intent to investigate and prosecute hacking crimes comes in the midst of growing international focus on Russia’s cyberattacks targeting Ukraine both before and after its full-blown invasion of its neighbor in early 2022. In March of last year, the Human Rights Center at UC Berkeley’s School of Law sent a formal request to the ICC prosecutor’s office urging it to consider war crime prosecutions of Russian hackers for their cyberattacks in Ukraine—even as the prosecutors continued to gather evidence of more traditional, physical war crimes that Russia has carried out in its invasion.

In the Berkeley Human Rights Center’s request, formally known as an Article 15 document, the Human Rights Center focused on cyberattacks carried out by a Russian group known as Sandworm, a unit within Russia’s GRU military intelligence agency. Since 2014, the GRU and Sandworm, in particular, have carried out a series of cyberwar attacks against civilian critical infrastructure in Ukraine beyond anything seen in the history of the internet. Their brazen hacking has ranged from targeting Ukrainian electric utilities and triggering the only two blackouts ever caused by cyberattacks to the release of the data-destroying NotPetya malware that spread from Ukraine to the rest of the world and inflicted more than $10 billion in damage, including to hospital networks in both Ukraine and the United States.

Though the Berkeley group’s submission initially focused on Sandworm’s 2015 and 2016 attacks on Ukraine’s power grid as the clearest example of cyberattacks with physical effects comparable to those of traditional warfare, it later expanded its argument to include Sandworm’s NotPetya cyberattack, as well as a third attempt by the hackers to sabotage Ukraine’s power grid and another cyberattack on the Viasat satellite modem network used by Ukraine’s military, which caused outages of the satellite modems across Europe.

[ad_2]

Source link